Suchen und Finden

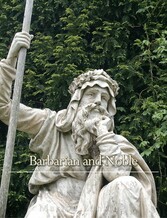

ALARIC THE GOTH

“THIUDANS! THIUDANS! (THE KING! THE king!)” So the Barbarians shouted as they raised on the shield, that he might be seen of all men, their newly chosen king, the fair-haired Alaric. They might shout as loudly as they pleased, for there were no Roman spies to hear. They had come away from Rome, across the broad Danube, and on their own plains, with the fresh mountain winds blowing upon them, they were renewing the traditions of their race and choosing a leader who should receive the glory of the Gothic name.

Trained in Roman legions in the years since the death of Athanaric, the young man Alaric had not forgotten that he was born on an island in the Danube. He had not lost the memory of the chill winds of the north, which were to the Goths the signs that they were in a free land. He had learned the lessons of war from the leaders of his enemy; he had risen to captaincy and had won notice from the general for his bravery. Now at the call of his people he had gladly turned his back on the warm southland, to have the breath of freedom blow across his face once more, and behold! to his astonishment they had chosen him king.

It was no secret among the barbarians that this choice was of a leader who could help them throw off the hated Roman yoke. The Romans were not the proud people of the days of Drusus. They had been too fond of power and of luxurious living. They had had too many strong barbarians to fight their battles for them, and had become content to sit idle in their palaces, drinking and gambling and scheming for wealth and position. The Gothic leaders had seen all this; they had come to scorn the conquerors whom once they had feared; and now they had chosen this tall, fair-skinned youth, who combined the strength of the barbarian with the warlike skill of the Roman captain, and bore moreover the prophetic name Alaric, Ala-reichs, which is to say, All-ruler.

The words of the old record concerning the beginning of his reign are full of meaning. “The new king, taking counsel with his people, decided that they should carve out for themselves new kingdoms rather than through sloth continue the subjects of others.”

Once and again Alaric led his people forth against the Romans. In Greece and Constantinople and in all the eastern possessions of Rome the name of “Alaric the Barbarian” became a word of terror. Then there came to him a strange call. As he was worshiping in a sacred grove he heard a voice repeating once and again these words, “Proceed to Rome, and make that city desolate.”

The young chief brooded over the message for many days, pondering whether he had been deceived by a dream. But ever the words rang in his ears, “Proceed to Rome, and make that city desolate,” and he felt a power within him urging him irresistibly on. He marshaled his armies and led them westward over the central plains of Europe, ravaging as he went. The Romans thought the march only one more barbarian invasion. The Goths were taking with them their women and children, but that was the curious custom of all barbarian nations. Their wars were for conquest of land, not for slaughter. If they won the battles they would stay and occupy the land with their wives and their children. Even the Gothic army did not believe that the purpose of Alaric would be carried out. Until he came to the passes of the Alps, to the gates of Italy itself, they doubted whether it could be possible that any barbarian nation would be permitted to meet the Romans in their own land. They had suffered many defeats by the way, and they had lost many brave warriors. Now the day had come when they must choose whether they would pass over into Italy or turn back to settle once again in their chill northern plains.

Alaric called a council, and the record of it, written in Latin on a roll of parchment, has been preserved to this day.

“The long-haired fathers of the Gothic nation, their fur-clad senators marked with many an honorable scar, assembled. The old men leaned on their tall clubs. One of the most venerable of these veterans arose, fixed his eyes upon the ground, shook his white and shaggy locks, and spoke:

“Thirty years have now elapsed since first we crossed the Danube and confronted the might of Rome. But never, believe me in this, O Alaric, have the odds lain so heavily against us as now. Trust the old chief who, like a father, once dandled thee in his arms, who gave thee thy first tiny quiver. Often have I, in vain, admonished thee to keep the treaty with Rome, and remain safely within the limits of the eastern realm. But now, at any rate, while thou still art able, return, flee the Italian soil. Why talk to us perpetually of the fruitful vines of Etruria, of the Tiber, and of Rome? If our fathers have told us aright, that city is protected by the Immortal Gods, lightnings are darted from afar against the presumptuous invader, and fires, heaven-kindled, flit before its walls.”

Alaric burst in upon the old man’s speech with fiery brow and scowling eyes:

“‘If age had not bereft thee of reason, old dotard, I would punish thee for these insults. Shall I, who have put so many emperors to flight, listen to thee, prating of peace? No, in this land I will reign as conqueror, or be buried after defeat. Only Rome remains to be overcome. In the day of our weakness and calamity we were terrible to our foes. Now in our power shall we turn our backs on those same enemies? No! Besides all other reasons for hope there is certainty of divine help. Forth from the grove has come once more a clear voice, heard of many, “Break off all delays, Alaric. This very year if thou lingerest not, thou shalt pierce through the Alps into Italy; thou shalt penetrate to the city itself."‘

“So he spoke, and drew up his army for battle.”

The victory must have been with the Goths that day, for the army went on through the passes into Italy, and ere long we hear of the barbarians as before the walls of Rome.

Then the whole world was in terror. That barbarians, skin-clothed barbarians, should have come to the gates of the great city, for six hundred years the ruler of the world, was a surprise to the barbarians themselves. To the Romans it was as if the sky had fallen.

Day after day the Gothic army lay encamped before the city, guarding the entrances that no food should enter by land or water; and hour after hour the Roman senate watched the north for the looked-for help from the army of the emperor, but none came. First the allowance of food to each person was reduced to one half; then to one third. Two noble ladies, who were entitled to draw from the imperial storehouses, gave of their portions to the people; but it was but a pittance among so many.

Then the proud Roman nobles sent out an embassy to Alaric. For all their need they did not cringe or beg. There is the sound in their words of the old days when Rome was mistress of all the world.

“The Roman people,” the message read, “are prepared to make peace on moderate terms, but they are yet prepared for war. They have arms in their hands, and from long practice in their use they have no reason to dread the battle.”

Alaric heard the words with a shout of laughter, and answered them with a Gothic proverb, “The thicker the grass, the easier mown.” The cultured Romans must have shrunk back with disgust from the rough, insolent barbarian with whom they were forced to treat. But their plight was desperate, and they must curb their pride and stay till the rude mirth had ceased and a fitting reply had been given to their message.

“Deliver to me all the gold that your city contains, all the silver, all the treasures that may be moved, and in addition all your slaves of barbarian origin; otherwise I desist not from the siege.”

“But if you take all these things,” said one of the ambassadors, “what do you leave for the citizens?” “Your lives,” returned Alaric with a grim smile. The message threw the Roman senate into the blackest despair. What was there left that they could do? The emperor had deserted them; even the God of the Christians, to whom they had recently sworn allegiance, seemed to have forgotten them. There was but one chance left. Perhaps their heathen gods who had helped their fathers in battle would aid them in this extremity. It is a weird scene that comes before us. On the Capitoline Hill, with Christian churches all about them, the Roman senate assembled to see the old ceremonies practiced, the old fires lighted, and the omens watched, by priests of the heathen faith which had been for a generation discredited. The hour passed and no help came. A second time the gates were opened and a train of suppliant Romans went forth to the camp of the conqueror to see what terms could be obtained.

It is a curious list of things which the barbarians wanted. It reminds us that they were after all but children—forest children—who fought because the desire for victory was on them, but knew not what to do with the power they won save to purchase for themselves toys and gay-colored trifles. Five thousand pounds of gold, thirty thousand pounds of silver, four thousand silken tunics, three thousand hides dyed in scarlet, and three thousand pounds of pepper,—these things Alaric would take in exchange for the city which he had conquered but had not entered.

The Romans went back to see how they could get these things. Was there as...

Alle Preise verstehen sich inklusive der gesetzlichen MwSt.